It is the fear of many strength athletes: losing strength and muscle mass during the (summer) holiday. A fear that we, strength athletes ourselves, know from our own experience. But also a largely irrational fear.

1. A training rest of two to four weeks, for example due to a holiday, can do no harm: neither for your muscle mass, nor for your strength level. Keep eating around your maintenance level and maintain a high protein intake (~2 g/kg/d).

2. Older strength athletes can afford a shorter rest break (about 2 weeks) compared to young gym goers (up to 4-8 weeks);

3. The fact that you start to look less muscular after a few days of training rest is due to the drop in glycogen levels in your muscles as a result of that rest. So it is an optical matter; you have not lost muscle mass.

4. After four weeks of inactivity, your muscle mass actually starts to decrease: slowly at first, gradually increasing speed. After three to four weeks, your strength level will also decline.

5. Regularly taking a longer period of training rest can also be useful, especially for advanced strength athletes. Deloading every five to six weeks (several days to a week) allows you to recover from cumulative fatigue and thus prevents overreaching and overtraining symptoms.

6. It takes about a third to half as long to regain strength and muscle as it does to lose strength and muscle.

TWO TO FOUR WEEKS OF REST

The maintenance or loss of muscle mass on the one hand and strength on the other during a longer rest period are fairly parallel to each other. Two weeks to a month of no strength training has hardly any consequences for both your muscle mass and your strength level, according to a large scientific review [i] [xxiv] . After all, your body does not ‘just’ break down muscle mass.

Age does play a role (see below): people in their forties and fifties already lose muscle mass from about two weeks, while youngsters can do without training for a month or even longer [xxv] .

Your muscle mass will therefore not decrease quickly under normal circumstances. Just make sure you eat at a maintenance level during the training-free period and that you still get enough protein (~2 g/kg/d).

VISUALLY LESS MUSCULAR?

If you don’t train for a while, you will probably look a little less muscular. However, this is not due to loss of muscle tissue, but because the glycogen stores in your muscles decrease [xv] . Glycogen is made from glucose (energy from carbohydrates) and is the main form of fuel for strength training. But if you stop training, those stocks no longer need to be replenished. The drop in glycogen levels sets in almost immediately when you stop exercising [xvi] .

After one week without training, glycogen levels can already be reduced by 20%. If you also consider that every gram of glycogen is stored with 3-4 ml of water [xvii] you can imagine why you look less muscular after a few days, even though the actual muscle mass has been preserved.

To maintain the glycogen levels in your muscles during your holiday (after all, you want to be able to parade tight on the beach) you can choose to regularly do push-ups and – if possible – pull-ups, possibly supplemented with other bodyweight exercises. If you want to be able to do some more exercises on vacation, take a set of resistance bands with you. Or book a hotel with a gym, after you have checked on Tripadvisor whether that gym also offers something.

REST FOR FOUR WEEKS OR MORE

The aforementioned research shows that muscle mass decreases from four weeks of training rest. Slowly at first, gradually getting faster.

Your body slowly adapts to your new ‘rhythm’, which lacks strength training and therefore, from a physiological point of view, also the need for (a lot of) muscle mass. As a result, the muscle cell volume decreases slowly and the proportion of muscle tissue type 2 decreases faster than type 1 [ii] [vi] . Type 2 is used to lift heavier weights, while type 1 is mainly used for lighter activities, such as endurance sports. The amount of muscle mass decreases faster the more time passes.

After four weeks you will also have to lose some strength [iii] . Count on five to ten percent. This is because your central nervous system, just like you, gets ‘lazy’ during your vacation.

REGAIN MUSCLE MASS

It takes about a third to half as long to regain strength and muscle as it does to lose strength and muscle, according to coach and author Greg Nuckols.

So if you haven’t been to the gym for six months, you should be able to regain the vast majority of the strength and muscle you lost within two to three months [xxvi] .

VARIABLE FACTORS

Whether and to what extent you lose muscle mass and strength during a rest period partly depends on a number of variable factors: training status, age and training technique.

TRAINING STATUS

Research from Columbia University in New York indicates that you lose muscle mass less quickly the longer you train. For example, someone who has only been on the irons for a few months will lose mass more quickly during a period without strength sports than someone who has been active for several years [iv] .

AGE

In most of the studies we cover in this article, the subjects were relatively young – mostly in their twenties. If you’re a bit older, you’ll probably lose your gains a little faster, especially if you’re over 65 [iii] [xxiii] . But people in their forties and fifties may also be able to afford less training rest. Unfortunately, this age group is rarely investigated in strength training studies.

Greg Nuckols thinks that older strength athletes can afford a shorter rest break (about 2 weeks) compared to young gym goers (up to 4-8 weeks) [xxv] .

The older you are, the lower your testosterone level, so the less anabolic support there is for muscle maintenance from your hormone balance. On the other hand, we already saw that the longer you train, the less quickly you lose your muscle mass, which could compensate for the age factor.

TRAINING TECHNIQUE

By this we mainly mean the range of motion (ROM) that you apply in your exercises. If you strictly stick to a full ROM during exercises, you will lose muscle strength and mass less quickly than if you only train with half movements. At least that is what Irish sports scientists discovered in test subjects who had them do biceps exercises [vii] . A sloppy execution can therefore lead to a faster loss in strength and mass.

DETRAINING AND REBOUNDING

Also in the long term, the effects of a solid training program remain in the body. This is mainly because your muscle tissue absorbs stem cells during strength training, and allows them to grow into new muscle cells. Those new muscle cells just stay in your muscles when you stop exercising [x] . As a result, there may be something like muscle memory, the phenomenon whereby after a period of detraining you temporarily build muscle mass faster than you did before that period [xxii] . In addition, after a longer training break you may be more sensitive to ‘old’ training stimuli (resensitization).

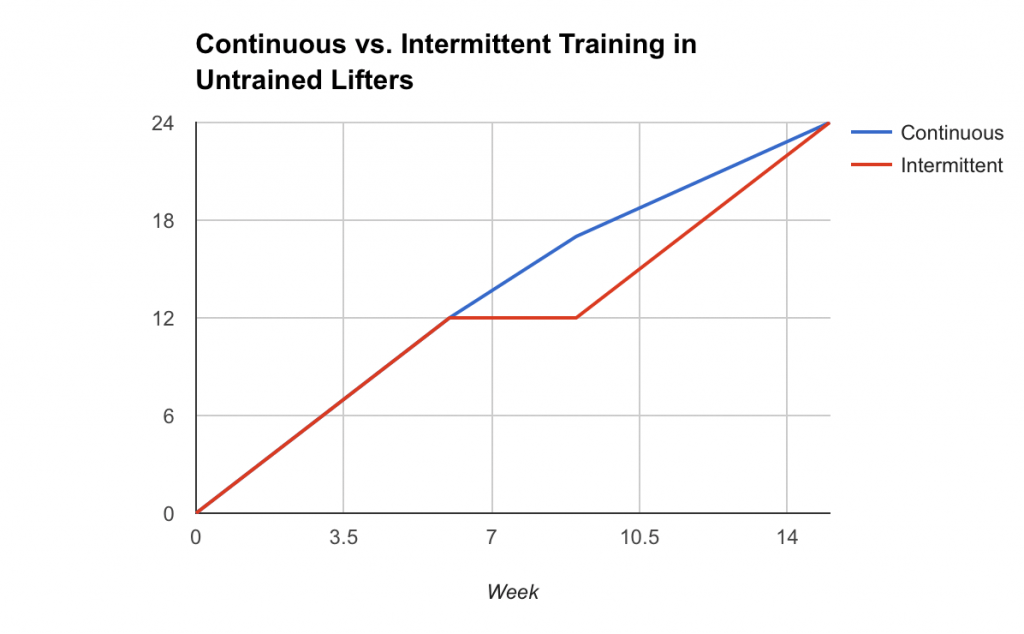

According to three studies, this effect of a quick rebound can even be so great that with periods of training rest you build up just as much muscle mass as if you had trained during those breaks [xiv] [xix] [xx] . For example, in one of those studies, one group trained for 15 weeks straight, while the other used the protocol for 6 weeks of training/3 weeks of rest/6 weeks of training. At the end of the ride, both groups had achieved approximately the same degree of muscle growth and strength gain. In the group that trained continuously, you saw the progression decrease in the last weeks, while the people in the ‘intermittent training’ group made the same progress as before the training break [xiv]. See image below.

Continuous training versus training with a break of three weeks: the result is the same. The units on the y-axis are arbitrary. (Source: Greg Nuckols, Stronger by Science )

Continuous training versus training with a break of three weeks: the result is the same. The units on the y-axis are arbitrary. (Source: Greg Nuckols, Stronger by Science )Important note about the studies in question: they were conducted among inexperienced strength athletes. The question is whether the rebound effect is just as great in more experienced strength athletes, since their overall training sensitivity is much smaller. On the other hand, they are probably less likely to lose muscle mass during a long period of training rest than beginners.

TRAINING REST CAN ALSO BE HELPFUL

Fanatic strength athletes are often horrified at the idea that they cannot train for a while. And that while training rest can, in the slightly longer term, actually take you further.

We already mentioned the deload. More advanced strength athletes have these as standard in their training rhythm, usually every five to six weeks. A deload allows you to recover from cumulative fatigue, the fatigue that builds up in muscles, tendons and joints over weeks of training.

If you never deload, sooner or later your body will not be able to recover sufficiently, leading to overreaching and eventually to overtraining. If you’re only going on vacation for a week, it can pass for deload just fine. You don’t have to keep training lightly when you’re deloading, unless you think it’s important to be able to walk around with ‘full’ looking muscles on holiday.

It is precisely advanced bodybuilders who sometimes consciously take training breaks, precisely to become more sensitive to ‘old’ training stimuli. This ‘trick’ is also known as strategic deconditioning. According to this theory, you need at least ten days of training rest to resensitize somewhat. Although it sounds nice on paper and its creator, coach Bryan Haycock, undoubtedly has good practical experience with it, this resensitization in bodybuilding training has not yet been scientifically researched [xxi] .

HOW MUCH CAN YOU KEEP WITH A LITTLE TRAINING?

You may be able to exercise occasionally for a longer period of time. Once or twice a week or so. Then you don’t have to worry about your muscle mass at all.

Research has shown that strength athletes between the ages of 20 and 35 may be able to maintain their muscles and strength for as long as eight months, while performing only one-ninth of their normal training volume [xxiii] . Older lifters (between 60 and 75 years old) can maintain their gains at a third of their usual training volume.

Greg Nuckols on this:

Something as simple as two to three sets of push-ups, pull-ups, split squats, and back raises, or hip thrusts per week should be sufficient to maintain the vast majority of your muscle and strength for a long, long time. [xxvi]

SUMMARIZED

A training rest of two to four weeks, for example due to a holiday, can do no harm: neither for your muscle mass, nor for your strength level. Keep eating around your maintenance level and maintain a high protein intake (~2 g/kg/d).

Older strength athletes can afford a shorter rest break (about 2 weeks) compared to young gym goers (up to 4-8 weeks);

The fact that you start to look less muscular after a few days of training rest is due to the drop in glycogen levels in your muscles as a result of that rest. So it is an optical matter; you have not lost muscle mass.

After four weeks of inactivity, your muscle mass actually starts to decrease: slowly at first, gradually increasing speed. After four weeks, your strength level will also decline.

Regularly taking a longer period of training rest can also be useful, especially for advanced strength athletes. Deloading every five to six weeks (several days to a week) allows you to recover from cumulative fatigue and thus prevents overreaching and overtraining symptoms.

It takes about a third to half as long to regain strength and muscle as it does to lose strength and muscle.

Originally published July 18, 2016, revised July 15, 2022.

REFERENCES

- [ i ] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sms.12047

- [ ii ] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8371654

- [ iii ] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23347054

- [ iv ] http://www.livestrong.com/article/383660-how-fast-do-you-lose-muscle-by-not-training/

- [ v ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28328712

- [ vi ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4120442/

- [ vii ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23629583

- [ viii ] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12173951

- [ ix ] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10795719

- [ x ] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20713720

- [ xi ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24586293

- [ xii ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2343230

- [ xiii ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20713720

- [ xiv ] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21771261/

- [ xv ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11252068

- [ xvi ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3160908

- [ xvii ] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11903130

- [ xix ] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23053130/

- [ xx ] https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.01161.2012

- [ xxi ] https://youtu.be/opDAn4PlYrk?t=3060

- [ xxii ] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/apha.13465

- [ xxiii ] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21131862/

- [ xxiv ] https://youtu.be/JjjrU9UUBv0?t=2704

- [ xxv ] https://youtu.be/JjjrU9UUBv0?t=2891

- [ xxvi ] https://barbend.com/how-to-return-to-strength-training-after-time-off/