It is a well-known phenomenon: when you are losing weight (or when you’re ‘cutting‘, as a bodybuilder), the fat loss will stagnate after some time. The pounds don’t fly off like they did in the beginning. Is it because your metabolism slows down, as is often claimed?

1. Metabolic adaptation, or adaptive thermogenesis, means that the body adapts processes in the body to better deal with the available energy. The phenomenon occurs when you eat much less or much more than usual for a longer period of time. Metabolic adaptation stems from the survival principles on the basis of which our body functions: if you eat much less, your body wants to survive. While you just want to lose weight.

2. Metabolic adaptation is mainly caused by the body cutting back on the energy consumption of non-sports, often unconscious physical activity (NEAT: Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis). In addition, it slightly saves on energy for basic processes, which slows down the resting metabolism.

3. The consequence of metabolic adaptation during a calorie-restricted diet is that the energy balance decreases. As a result, you gradually have to eat less and burn more and more to maintain the energy deficit. This can lead to fatigue and possibly also to a decline in exercise performance. The latter can promote loss of muscle mass.

4. The degree of metabolic adaptation varies greatly from person to person. As a result, some people have more trouble losing weight than others.

5. Metabolic adaptation does not alter the calories in, calories out princible: as long as you eat fewer calories than you expend, you will lose weight.

6. You can limit the extent and consequences of metabolic adaptation by not cutting for too long and/or by using non-linear diet strategies, such as refeeds and diet breaks. Moreover, to a certain extent you can influence your NEAT by consciously moving more ‘spontaneously’, such as walking, standing and climbing stairs.

WHAT EXACTLY IS METABOLISM?

Metabolism is, simply put, the set of processes that your body carries out to keep you alive and to support your physical activities. To this end, it uses the energy you ingest in the form of food. Although metabolism and energy expenditure are not strictly the same, they are often seen as such.

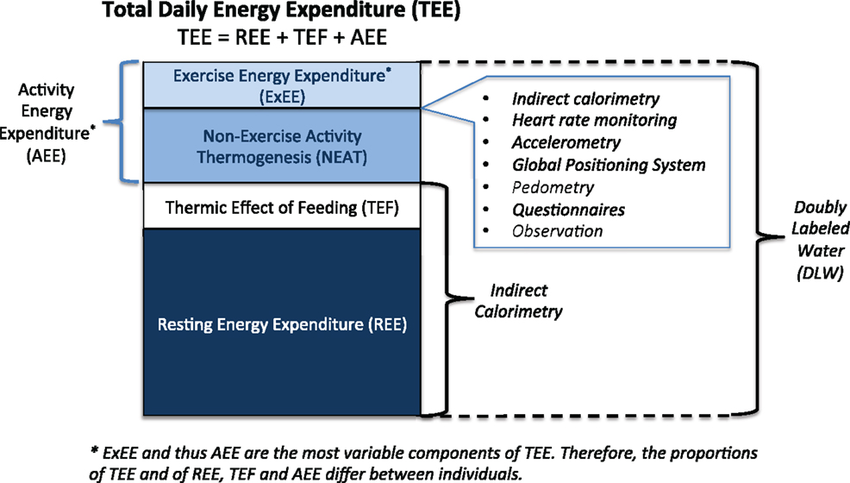

How is our daily energy consumption structured? About 70% goes to basal metabolism (also known as Basal Metabolic Rate, abbreviated BMR) [ i ] . That is the energy that is necessary for the primary life processes that take place in the organs. You also often hear the term “resting metabolic rate” (or Rest Metabolic Rate, RMR, or Resting Energy Expenditure, REE), which is not formally quite the same as basal metabolic rate. We’ll leave out the minor differences between those two terms for now, except that BMR is slightly more accurate than RMR/REE.

About 10% of your energy is needed for processing food, also called thermogenesis, or thermic effect of food (TEF). People often think that metabolism is mainly the digesting food (digestion), but you see, it is only a small part of it.

The other 20% of your daily energy expenditure covers all your physical activities: from standing up to doing strength training. This also increases the metabolism, because all kinds of processes take place in the body to support those activities and let you recover from them. We can again subdivide the physical activities (Activity Energy Expenditure, AEE) into NEAT and ExEE.

All physical activities except sports, sleeping and eating are also called Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT). Think of walking, standing up, typing, shopping, cleaning, working in the garden, turning on your chair and so on. The share of NEAT in the total energy consumption can differ greatly from person to person, partly depending on the way in which life is fulfilled (eg the type of work) [ xx ] .

The energy expenditure caused by exercise (not only during exercise itself, but also for recovery afterwards) is also called Exercise Energy Expenditure (ExEE), or Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT).

How your daily total energy expenditure (TDEE = Total Daily Energy Expenditure) is structured. Source: Hills et al, Assessment of Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure: An Overview of Objective Measures (2014) .

How your daily total energy expenditure (TDEE = Total Daily Energy Expenditure) is structured. Source: Hills et al, Assessment of Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure: An Overview of Objective Measures (2014) .The difference between NEAT and EAT is not always clear. If you walk 2 kilometers every day, for example because of your work, that energy consumption belongs to NEAT. But if you consciously walk 2 kilometers to burn calories, you should count that as EAT.

METABOLIC ADAPTATION

When you are losing weight or cutting, your body is in a negative energy balance for a long time – sometimes for weeks or even months: you should be taking in fewer calories than you use. That’s how you burn fat. But your body gradually does exactly what you don’t want: become more efficient with energy, so that you lose weight less and less quickly. It therefore adapts to the amount of energy available to it.

This phenomenon, which is scientifically fairly well documented, is called metabolic adaptation or adaptive thermogenesis [ v ] . Your body simply thinks in terms of survival and doesn’t take into account your desire to burn fat.

HUNGER MODE?

The terms ‘starvation mode’ or ‘starvation mode’ are also commonly used for metabolic adaptation. However, these are not correct, as they suggest that the metabolism only slows down when you are hungry. But with ‘normal’ weight loss or cutting in, there is normally no real hunger or malnutrition at all. The metabolism slows down just as much with smaller calorie reductions, just as it speeds up when you eat more. The term ‘economy mode’ covers the load better.

ANYONE CAN LOSE WEIGHT

The degree of metabolic adaptation varies enormously from person to person and is therefore difficult to predict. This makes it difficult to say in advance how low a caloric intake should go to lose fat. And because of this, one person has much less trouble losing weight than the other. However, the regulation of hunger and a person’s relationship with food also play a role.

Metabolic adaptation does not alter the calories in, calories out princible: as long as you eat fewer calories than you expend, you will lose weight. Period. So metabolic adaptation is primarily something to be aware of, not something to be afraid of — anyone can lose weight.

WHAT METABOLIC ADAPTATION IS NOT

When you are cutting, you eat less and your body weight decreases. These things in themselves already have a certain influence on your energy consumption. But that happens automatically and it is not what we understand by matabolic adaptation.

LESS MASS = LESS ENERGY CONSUMPTION

The greater your body mass, the more energy your body needs to ‘maintain’ that mass and therefore the faster your metabolism is. When you lose weight, that mass decreases – if all goes well, only fat mass. As a result, your body has to perform less maintenance work. With the disappearance of the kilos your energy consumption decreases [ xv ] . This effect should not be exaggerated: per kg that you lose, the body would burn 12.8 kcal less per day [ xvi ] . So if you’ve lost 10 pounds, your body burns 128 fewer calories per day purely on that basis.

The fact that your fat mass decreases is of course exactly what you want and you have to accept the small metabolic consequences of this. Make sure that your muscle mass remains intact as much as possible when you are losing weight. Maintaining muscle mass costs more energy (about 13 kcal/kg body weight/day) than maintaining fat mass (4.5 kcal/kg body weight/day), so for that reason it is so important for a bodybuilder to maximize muscle mass during the cut. to hold on. Moreover, the larger the muscles, the more insulin receptors they have and therefore the more insulin sensitive they are. And that in turn means that your body is less likely to store carbohydrates as fat [ viii ] .

LESS FOOD = LESS ENERGY CONSUMPTION

Because you (always) eat less than normal during weight loss or cutting, the body (always) needs less energy for digesting and absorbing food. So you benefit less from the thermal effect of food, or the thermogenesis or TEF that we just mentioned. The impact of this is relatively small, because TEF only accounts for 10% of your total energy consumption.

By the way, you can do a few (small) things to maintain or increase thermogenesis. First of all, eat a lot of protein (~1.8 g/kg body weight/day), but you already do that to protect your muscle mass. The thermic effect of proteins (20-35%) is greater than that of carbohydrates and fats (5-15%), ie digesting proteins takes more energy than is the case with carbohydrates and fats. If you have consumed proteins with a thermal effect of 25%, that means that of the 100 kcal of those proteins, 20 kcal are used for processing.

In addition, you can stimulate thermogenesis by choosing certain foods. For example, put a lot of natural or unprocessed foods on your menu. These products contain dietary fiber and are difficult to digest. As a result, your body has to work extra hard to break down the fibers. A 2010 study shows that the thermic effect of unprocessed food can be almost twice that of processed food: 10.7% for the processed food (white bread with processed cheese) compared to 19.9% for the unprocessed food ( multigrain bread with cheddar cheese) [ ix ] . Red peppers, legumes, cocoa and apple cider vinegar are also known for their great thermal effect. Like caffeine, in the form of coffee or a supplement, a fat burner possibly.

Finally, ‘grandma’s tip’: drink cold water. Its relatively large thermal effect has been demonstrated by a few studies [ iii ] [ iv ] , although it is often exaggerated. Apart from other (alleged) benefits of drinking a lot of water, it is probably little more than a drop of water for the metabolism.

An often mentioned strategy to boost thermogenesis and thus metabolism is to spread food intake over as many eating moments as possible. But you probably know by now that that was a widespread myth: the energy expenditure through thermogenesis is only about the total food intake, not about its distribution. A higher meal frequency, at least with regard to metabolism, therefore provides no benefit, as has been shown by research.

HOW QUICKLY DOES THE BODY ADAPT?

Science has not yet really provided insight into how quickly and to what extent metabolic adaptation generally occurs. Classic studies into malnutrition, from the 1960s and 1970s, did show that consuming a mere 450 calories per day reduced energy expenditure by up to 45 percent [ vii ] .

But it is not entirely clear whether metabolic adaptation kicks in immediately as soon as you reduce your calorie intake. Research from the 1980s suggests that when fasting, the body begins to adjust energy expenditure only after 72 hours (3 days) [ xvii ] . In fact, your body seems to make hormones that temporarily speed up metabolism by about 14 percent in acute calorie reduction [ xviii ] . But then we are talking about fasting. However, a 2015 study shows that if you cut your calorie intake by 50%, adaptive thermogenesis kicks in immediately [ xix ] . In other words, your metabolism will slow down on the first day of your diet.

According to author Lyle McDonald, when and how quickly metabolic adaptation starts varies greatly from person to person. Moreover, rapid adjustment in the event of a calorie deficit does not mean that your metabolism also adapts quickly if you start eating more (again). If you are genetically unlucky, you have a fast adaptation to a calorie reduction and a slow adaptation to a calorie increase. The other way around is also possible – then you are lucky [ xxi ] .

If you adapt quickly, you should quickly reduce your calorie intake further. However, do not try to dive below 1200 kcal, at least not for a long time. That is the minimum number of calories you need daily to get all the necessary nutrients from different sources [ xiii ] . In addition, you need sufficient carbohydrates to maintain your training performance. And these are important to prevent loss of muscle mass.

CAUSES OF METABOLIC ADAPTATION

What are the causes of metabolic adaptation? And what can you possibly do about it?

1. ADAPTING ENERGY FOR ‘SPONTANEOUS’ ACTIVITIES (NEAT)

Yes, our bodies are smart enough to cut back, if necessary, on the energy spent on spontaneous activities, the just discussed non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). It is unclear what mechanisms underlie this [ x ] . It is probable, however, that cutting back on NEAT is by far the most important cause of metabolic adaptation and therefore not cutting back on the resting metabolic rate (see 2), as is often thought.

What can you do about it?

Too little is known about NEAT to know how you could counteract slowing down of this part of your metabolism. But you can of course make sure that you keep moving sufficiently ‘spontaneously’. That you take the bike instead of the car, take the stairs instead of the elevator, and that you stop instead of sitting down. It is quite possible that you consciously or unconsciously cut back on these kinds of physical activities when you are energy deficient. Use the pedometer on your mobile phone to become aware of how much you walk in a day.

However, much of the NEAT involves unconscious, spontaneous movements, such as blinking the eyes. Unfortunately, metabolic adaptation cannot be stopped at this point. So you will have to accept that your body cuts back on your energy consumption and that you gradually have to eat (even) less in order to maintain a certain energy deficit.

Doing cardio does not increase the NEAT, because that is sport and we therefore count it as part of the other part of the active metabolism (ExEE).

2. ADJUSTMENT OF BASAL ENERGY (REE)

More efficient use of energy also means a slower resting metabolism (BMR/RMR/REE). So the body cuts down on the basic processes in your body that are necessary to keep you alive. As already mentioned, however, this only covers a small part of metabolic adaptation.

What can you do about it?

Unfortunately, there is very little you can do about cutting back on your resting metabolism. You may still need to improve your sleep. By sleeping well and for a long time, you maintain the level of the thyroid hormone T4. Thyroid hormones have a stimulating effect on the metabolism. They stimulate the body cells of various organs to use more energy.

CONSEQUENCES OF METABOLIC ADAPTATION

Through metabolic adaptation, or saving mode, your energy consumption and therefore your maintenance level decrease: your body needs fewer and fewer calories to keep you ‘alive’.

Suppose your maintenance is 2500 kcal. You are going to cut and cut 500 calories, which means that you have to reach 2000 kcal below the line. But due to metabolic adaptation, your maintenance over time is only 2000 kcal. Result: to create a deficit of 500 kcal, you can now only eat 1500 kcal (2000-500). If you continue to eat 2000 kcal, the original level, there is no longer an energy deficit. To burn fat again, you will have to eat even less and/or do (even more) cardio. Something that sooner or later will hardly be possible. After all, you also need energy for your strength training.

Metabolic adaptation therefore means that you usually have to diet longer and eat less than you would like. If you, as a bodybuilder, also have to do strength training, that can be quite a challenge. After all, a long-term energy deficit leads to so-called diet fatigue , which can manifest itself in hunger, having less energy, a decline in strength performance, and a lower testosterone level, resulting in a lower libido. Prolonged dietary fatigue also promotes loss of muscle mass and that is of course the last thing you want.

REMEDIES AGAINST METABOLIC ADAPTATION

You cannot stop metabolic adaptation, although we saw that it occurs much more strongly in one than in the other. However, there are strategies that can help you cope better and thus limit dietary fatigue.

1. DON’T CUT TOO LONG

The best remedy for metabolic adaptation is simply not dieting or cutting for too long. After all, the adaptive response gets stronger and stronger, so that you may eventually have to use a calorie level that is unpleasant, or that your strength performance in the gym will suffer. As a bodybuilder it is therefore better to do minicuts, cut cycles of at most one or one and a half months. Then you can normally lose a good amount of fat, without experiencing many other mental and physical adverse effects.

Shortly cutten is only possible when you last row brims and additionally lean teeming, ie to adequate training stimulus sets a restricted calorie surplus (~ 200-500 kcal).

2. NONLINEAR DIETS

If you still need a longer time to lose fat mass, it is best to use a non-linear diet approach. That means on some days or for certain periods of time, you have a higher calorie intake, usually at the maintenance level. The best known methods are refeeds and diet breaks.

A refeed will have to take at least three days to bring about any recovery in metabolism and hormone levels. Although one day of refeeding can in principle also bring about something positive, such as a small, very temporary boost in energy and perhaps a small mental boost.

A diet break usually takes a minimum of one week. So, for example, maintain a calorie deficit for three weeks and eat maintenance for one week.

3. DO CARDIO

Some people find it easier to maintain their diet if they significantly increase their energy expenditure by doing some form of cardio. After all, more consumption means that you can eat more. If you feel comfortable with that, fine.

However, that is no way to reduce metabolic adaptation, because on balance your energy level will be the same if you would not do any cardio but eat less. In addition, people often tend to compensate for cardio, consciously or unconsciously – by eating more and/or exercising less spontaneously [ xi ] [ xii ] .

As a bodybuilder, you should not do too much cardio anyway if you follow an energy-restricting diet. This can interfere with the recovery of your strength training, which can lead to loss of muscle mass.

WILL THE METABOLISM RECOVER?

We have seen that your body is perfectly capable of adapting your energy consumption to a new situation, in this case that of an energy shortage. Fortunately, it also works the other way around: if you increase your energy balance again, your energy consumption will accelerate again. This normally happens within a day or three, but we have also seen that this happens significantly faster for some than for others.

That long-term weight loss would cause permanent damage to the metabolism is a myth: there is no such thing as ‘metabolic damage’ [ xiv ] .

Make sure that you increase your calorie intake slowly, i.e. step by step, when you finish the cut and not all at once (also called reverse dieting).

IN SUMMARY

With a long-term energy deficit, your body will use energy more efficiently. As a result, you will burn less and less fat at a certain energy balance. You will therefore have to gradually lower your energy balance in order to continue to lose weight at the same rate. If that becomes too difficult, you can take shorter or longer diet breaks to bring the energy consumption back to normal levels.

Your body mainly saves on the energy consumption of non-sports, often unconscious physical activity (NEAT: Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis). In addition, it saves somewhat on energy for basic processes, in other words on the resting metabolism.

Strictly speaking, the expression “slowing down the metabolism” is therefore not entirely correct. During dieting, your body will use energy more efficiently and the energy consumption of the resting metabolism is only a relatively small part of this: it mainly concerns the NEAT.

To a certain extent you can influence your NEAT by consciously moving more ‘spontaneously’, such as walking, standing and climbing stairs.