Training intensity means how heavy you train. But ‘heavy’ is open to various interpretations. A high weight can be heavy, but delivering a great effort with a light weight also. Let’s clarify exactly what intensity means in bodybuilding training, and how best to apply this training variable.

1. Absolute intensity (load) is the training weight you use, usually expressed as a percentage of your 1RM.

2. Relative intensity (effort, or intensity of effort) is the effort you make during a set, which is the extent to which you train until muscle failure, usually expressed in Reps In Reserve (RIR).

3. In theory you can achieve optimal muscle growth with both light and heavy weights, provided you train no lighter than with 30% of your 1RM. The degree of muscle growth is therefore mainly determined by your effort. The greater the effort, the more ‘effective reps’ it produces. And it is especially those effective repetitions that stimulate muscle growth.

4. For practical reasons, it is best to use weights between 65 and 85% of your 1RM, or weights with which you can do 6 to 15 repetitions. If you are more advanced, it can be beneficial to also do some work outside of that rep range.

5. Train your sets to near muscle failure, but usually not to complete failure. Keep 1-3 reps ‘in the tank’ (1-3 RIR), especially for compound exercises. Isolating exercises can be trained more often to complete muscle failure.

INTENSITY, AN IMPORTANT TRAINING VARIABLE

Training intensity (how hard you train) is an important training variable in bodybuilding training, in addition to training volume (how much you train) and training frequency (how often you train).

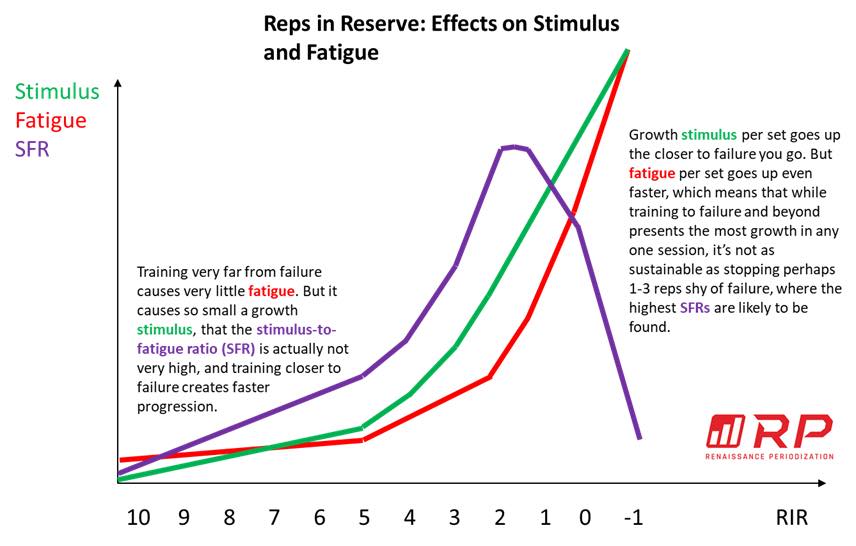

These three variables influence each other. As a natural bodybuilder, the trick is to find the optimal ratio between the training variables, so that you create the greatest possible growth stimulus with the lowest possible fatigue. In technical terms: with which you achieve the most favorable stimulus to fatigue ratio (SFR).

TWO KINDS OF INTENSITY

The confusing thing about training intensity is that there are two types: absolute and relative. And in practice, these are often used interchangeably. Or people ‘forget’ that there is also a relative intensity. While that, for muscle growth, is the most important.

ABSOLUTE TRAINING INTENSITY (LOAD)

Absolute intensity (also called load) refers to the load, or resistance. In fact, the number is on the dumbbell or weight plate, although absolute intensity is – confusingly enough – usually expressed relatively, namely as a percentage of the one-rep max (1RM), the weight with which you cannot do more than one repetition. For example, with a weight of 85%1RM you will be able to do about five reps. The reason for this relative notation is obvious: what is a heavy weight for one person is not (anymore) for another.

How heavy you can lift depends on the one hand on your physique, on the other hand on your training status (beginner, intermediate, advanced). There are certain strength standards based on training status, but be aware that these are based on powerlifting, a fundamentally different kind of strength sports than bodybuilding.

Absolute intensity is the load, or training weight you use, usually expressed as a percentage of your 1RM.

RELATIVE EXERCISE INTENSITY (EFFORT, OR INTENSITY OF EFFORT )

The heaviness of a weight does not say much from a training perspective. Let’s say you pick up a weight of 65% of your 1RM, which you can complete about 15 reps in a row. So at roughly the sixteenth repetition you will reach muscle failure, the moment when you can no longer do a full repetition. However, you stop your set at ten repetitions and therefore leave at least five repetitions. Have you trained hard? Not really. The heaviest reps of a set are the last five or so before muscle failure. The shorter you get to muscle failure, the greater the effort.

The degree to which you train to muscle failure during a set is the relative intensity, also called intensity of effort or simply effort. This training variable therefore indicates how much effort you put in during a set, regardless of the weight of the weight you use (the absolute intensity).

Effective reps

How relative intensity works is nicely illustrated by the following. The last repetitions before muscle failure, the red ones, cause the greatest mechanical tension, the main training mechanism behind muscle growth. These repetitions provide the greatest growth stimulus and are therefore also called stimulating or effective repetitions.

It’s about the reps that feel the heaviest, regardless of the weight and number of reps you use in a set. (Source: YouTube / Radu Antoniu)

It’s about the reps that feel the heaviest, regardless of the weight and number of reps you use in a set. (Source: YouTube / Radu Antoniu)Expressing relative intensity in RIR and RPE

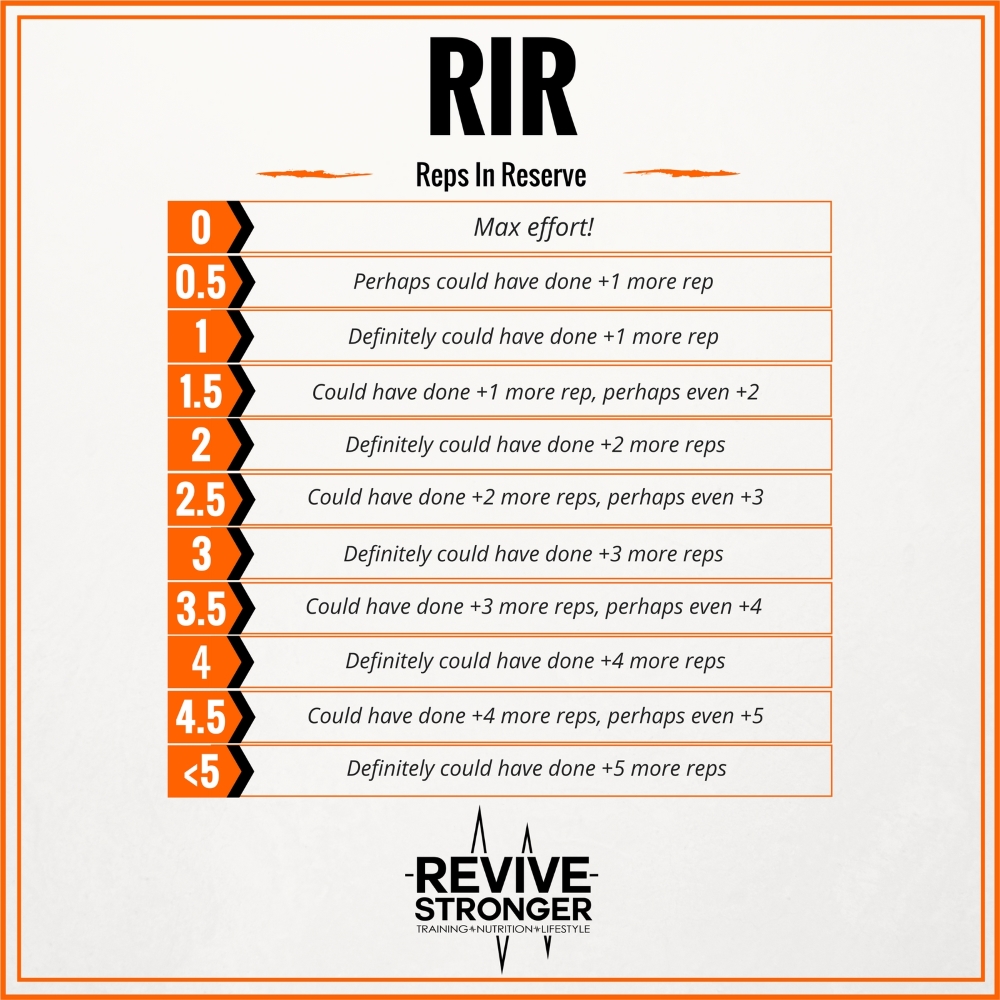

Relative intensity is nowadays usually expressed in Reps In Reserve (RIR). For example, 2 RIR means that you stop a set when you could do two more complete reps (for example, just before rep 14 in the first column in the figure above). You keep two reps in the tank, so to speak.

At 0 RIR you can no longer do a full repeat. However, 0 RIR is not the same as training to absolute muscle failure. That’s when you get stranded during a replay. For example, if you try to lift the weight again during a biceps curl, but you can no longer continue halfway through that (concentric) movement. We denote this as -1 RIR.

It is quite difficult to properly estimate RIR; it requires at least some training experience.

The less Reps In Reserve, the greater the effort you put in during a set. (Source: Revive Stronger)

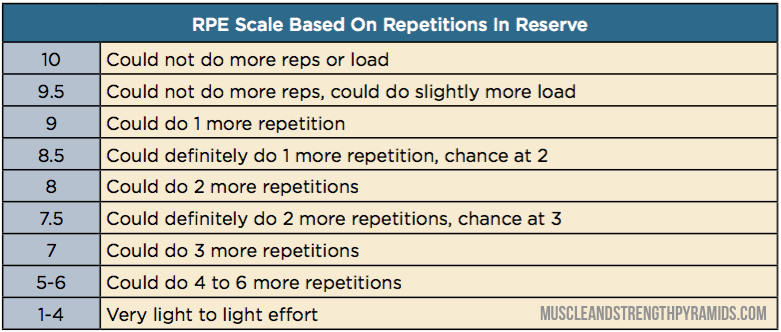

The less Reps In Reserve, the greater the effort you put in during a set. (Source: Revive Stronger)Relative intensity is also sometimes expressed in RPE, or Rating Perceived Exertion. RPE was devised fifty years ago to determine training stress during endurance training. Later, the scale was projected on doing sets in strength training and the amount of RIR involved. Scientist and author Eric Helms tells more about it on this page, where you will also find the RPE table below.

The principle of RPE is the same as RIR, only now there is an increasing value, which may make more sense if you want to express a degree of effort.

Rating Perceived Exertion, applied to strength training and the number of reps away from muscle failure (Reps In Reserve). (Source: The Muscle and Strength Pyramids)

Rating Perceived Exertion, applied to strength training and the number of reps away from muscle failure (Reps In Reserve). (Source: The Muscle and Strength Pyramids)Relative intensity is the effort you make during a set, or the extent to which you train to muscle failure, usually expressed in RIR (Reps In Reserve) and sometimes in RPE (Rating Perceived Exertion).

WHICH INTENSITY IS MOST IMPORTANT?

We have seen that muscle growth is mainly caused by the effective repetitions in a set, which after all generate the greatest mechanical stress. And you can accomplish those effective reps with both light and heavy weights. With light, you’ll just have to do more reps.

Many studies have now shown that the training weight for muscle growth in principle makes no difference: you can build muscle mass with both light and heavy weights. The only caveat is that the weight should not be less than 30% of your 1RM. In addition, it is important that you make sufficient effort: as a rule 1-3 RIR (see below), but with light weights (30-50%1RM) you probably have to train until complete muscle failure to create an adequate growth stimulus.

Dit bericht bekijken op Instagram

When training for muscle growth, it is therefore primarily about the relative intensity – the height of the training weight, the load, is subordinate to this. In short:

It is true, however, that heavy weights are most effective for getting strong (in order to increase your maximum strength), while you train your strength endurance with light more. Bodybuilders who want to become both muscular and strong (we call them powerbuilders actually) therefore choose relatively heavy weights anyway.

If strength is not really important for you, then in principle you have complete freedom in choosing the training weight and the corresponding rep range. That is good news for those who cannot train with heavy weights, for example because of or to prevent injuries. After all, remember that heavy weights put a lot of strain on your tendons and joints, which is why older bodybuilders train better with lighter weights anyway. However, don’t forget that you also have to make progress with lighter weights in order to grow and will therefore have to add weight along the way.

In theory you can achieve optimal muscle growth with both light and heavy weights. After all, the degree of muscle growth is determined by the relative intensity and the number of effective repetitions that it produces. Effort is therefore more important than load for muscle growth.

WHAT IS THE OPTIMAL ABSOLUTE INTENSITY?

Although in theory you can build muscle with both light and heavy weights, best is to train with medium heavy weights, i.e. between 65 and 85% of the 1RM. These are weights that allow you to do anywhere from 6 to 15 reps. This is mainly for practical reasons.

For example, with very light weights (30-50%1RM) it is much more difficult to create a sufficient growth stimulus, because the cardiovascular fatigue often leaves you stranded well before you have reached the point of muscle failure. Doing very long sets is simply not an efficient and pleasant way of training, and also causes a lot of central fatigue.

With very heavy weights (>85%1RM) you can do too few effective reps, which you will have to compensate by doing more sets – also not very efficiently. In addition, it is more difficult to make a good mind-muscle connection, your tendons and joints have to endure more, and you have a higher risk of injuries.

So 6-15 is the best rep range in our opinion, with 6-10 reps for compound exercises and 10-15 reps for isolation exercises. But it is of course not forbidden to train outside this spectrum. In fact, advanced bodybuilders in particular may benefit from taxing a muscle in different rep ranges, so to do some work with <6 and >15 reps as well.

For practical reasons, it is best to use weights between 65 and 85% of your 1RM, or weights with which you can do 6 to 15 repetitions. Although it is fine and even advisable for more advanced athletes to also do some work outside this range.

WHAT IS THE OPTIMAL RELATIVE INTENSITY?

Opinions have traditionally been divided about how much effort you should make during a set. There is a great temptation to think that you have to train all sets to the limit, but in many cases that can be counterproductive.

Research shows that training to muscle failure causes disproportionate fatigue, which negatively affects your recovery capacity and your next training performance. By ‘disproportionate’ we mean that the extra growth stimulus from training to muscle failure does not outweigh the extra fatigue.

If you leave one or a few repetitions ‘in the tank’ (1-3 RIR) you achieve almost as much muscle growth, but at a much lower fatigue. This allows you to do more productive sets (volume), so that on balance you can do more effective repetitions and thus build more muscle mass.

You create a growth stimulus by doing enough sets and by making sufficient effort per set, so by training until (near) muscle failure.

You create a growth stimulus by doing enough sets and by making sufficient effort per set, so by training until (near) muscle failure.Most coaches nowadays are therefore in favor of not training until muscle failure, but in most cases using 1-3 RIR (or RPE 7-9). In this way you probably achieve the most favorable Stimulus Fatigue Ratio (SFR) and therefore the fastest muscle growth. Only with isolating exercises you can safely train until muscle failure more often. With very long sets, with light weights, you probably must train until muscle failure to create sufficient growth stimulus.

You achieve the best Stimulus:Fatigue Ratio (SFR) by training about two repetitions of muscle failure (2 RIR). (Source: Mike Israetel/Renaissance Periodization)

You achieve the best Stimulus:Fatigue Ratio (SFR) by training about two repetitions of muscle failure (2 RIR). (Source: Mike Israetel/Renaissance Periodization)If you do opt for a high-intensity approach – in which you train each set until muscle failure – make sure you adjust your training volume accordingly and that you use a longer recovery time between training sessions of the same muscle group. This approach may be especially helpful if you’re short on time, or want to resensitize your body to volume.

If you often train to muscle failure, you will experience a disproportionate amount of fatigue. The relative intensity is then at the expense of the volume, so that on balance you can do less effective repetitions. That’s why it’s best to keep a few reps in the tank for most sets (1-3 RIR, RPE 7-9).

IN SUMMARY

When training for muscle growth you have to take into account the absolute intensity (the training weight, usually expressed as a percentage of your 1RM) and the relative intensity (the effort you put in during a set, i.e. the extent to which you train to muscle failure, usually expressed in RIR ).

You can implement these variables in your training as below.

| Training form | Reps | RIR | Rest |

| Compound Exercise | 6-10 | 1-3 | 2-5 minutes |

| Isolating exercise | 10-20 | 1-2, sometimes muscle failure | 1-2 minutes |